The level of interaction between teachers and children can look wildly different from one child care center to the next, or even one classroom to the next. In visits to centers around the country, I’ve found lunchtime can be a great indicator of how things go throughout the day, especially for toddlers. Some lunchtimes are highly interactive. Teachers sit with the children, eating with them and taking opportunities to ask questions about the temperature and texture of the food. In other centers, I’m struck by the quiet. Children sit around small tables eating their meal or snack, but there’s no interaction between them and their teachers. Clearly not from any lack of warmth or caring on the part of the teachers, but it always seems to me to be a missed opportunity for engagement. Early on as we began applying LENA in child care settings, these contrasting lunchtimes concerned me. Knowing what we now know about the critical importance of interactive talk between adults and children during the earliest years, I wondered what insights the data might hold.

Recent findings from a sample of LENA Grow classrooms confirmed that what I have observed was far from atypical and uncovered what could be a serious issue for those concerned about child care quality and school readiness. In short, the early data is actually worse than I feared, and it goes beyond lunchtime. Aggregated data from this exploratory subset of infant and toddler child care classrooms reveals that more than a third of children experienced just four or fewer talk interactions per hour with a caregiver for the vast majority of their day, effectively spending almost all of their day in isolation. We know this because LENA’s “talk pedometer” technology quantified the amount of conversational turn taking each child experienced throughout the day in these classrooms.

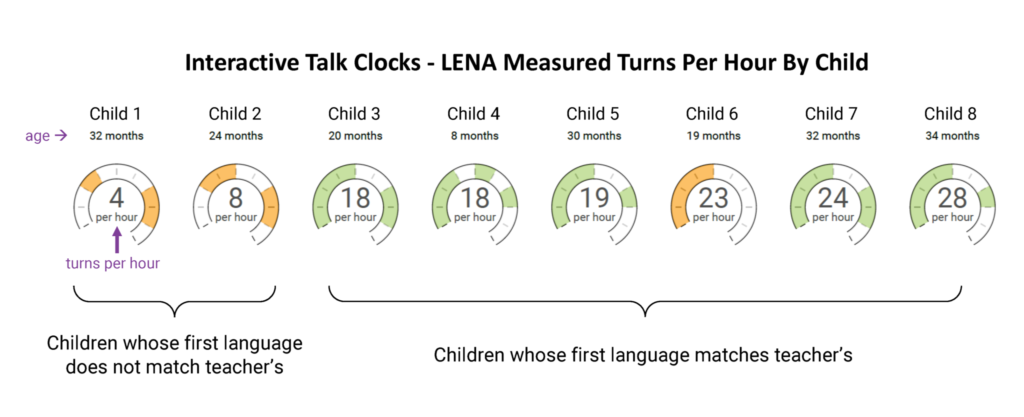

In addition to the overall finding that many children experienced what we are calling “language isolation,” large disparities appeared within these classrooms, revealing that exposure to talk varies significantly from child to child. In some cases, these child-to-child disparities arise when children who are dual language learners do not speak the same language as their teachers. In one example, a pair of non-English-speaking toddlers had less than a third of the number of turns as the six other English-speaking children in the same room (see graphic below).

So, is this a national issue, or can these findings be confined to the set of classrooms in this exploratory analysis? The picture is unclear.

While the field is now turning more attention to the needs of infants and toddlers in child care, there remain many questions about how to measure quality in these early care and education settings and what quality looks like. The years before age 3 are extremely consequential for future development and learning, and the amount of interactive talk a child experiences before the age of 3 affects vocabulary acquisition, kindergarten readiness, third-grade literacy, and academic and social–emotional outcomes into adolescence. It’s time to know more about conversational interactions in infant and toddler classrooms across the country.

Rather than being dismayed about this challenge, we should be energized and optimistic. With recognition can come a response, and there are a number of current opportunities to better understand and address the issue of language isolation. First, the Administration for Children and Families at the Department of Health and Human Services, jointly with the Department of Education, awarded more than $240 million in Preschool Development Grants Birth through Five Grants (PDG B–5) to 43 states, the District of Columbia, and the US Virgin Islands. The PDG B–5 investment provides an amazing opportunity for awardees to better understand infant and toddler classrooms in their states, assess the needs of providers, and develop a strategy to truly move the needle on equitable access to high-quality early care and education for all. LENA will be contributing to several states’ efforts, simultaneously supporting needs assessments by measuring the amount of talk in infant and toddler classrooms while also building the capacity of programs to offer language-rich early learning environments to our youngest children. In addition, the J.B. and M.K. Pritzker Family Foundation is also putting funding behind this issue with a prenatal-to-age-3 state grant competition that starts with a planning grant followed next year by an action grant.

There’s much work to do, but with the right data-informed strategies, we can look forward to a time when every child’s day is filled with wonderful, nourishing conversation. We are optimistic that states will use these opportunities to better understand and support quality in infant and toddler settings, and we feel inspired at the thought of being able to contribute to the field’s understanding of what is most important for the nation’s youngest children.

[about]